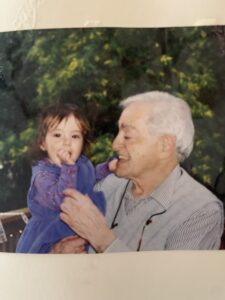

I wrote this poem years ago, about my father, Joseph Serra. Sharing this again today, on his birthday. He would have been 98. We were blessed with his gregarious, loyal and brave presence until he was almost 83. He did a lot of wonderful things in his life – raised by a single mother who did not speak English, after he fought in the war her returned and he eventually became a champion of public education– first to graduate high school, college, graduate school. He was a loving spouse in the face of much adversity, awesome uncle to many nieces and nephews, and most of all, an obsessively devoted devoted father and grandfather. Those early years of four kids under ten, his wife fighting a tough debilitating disease and making it all work on a public educators salary, he must have felt like Cicero. But I have many happy memories of picking basil in the garden, playing in the local pool, camping all over the country and debating everything under the sun at the dinner table. I think we all still miss him, and my mother, daily. But the warm stories take away any lingering sting or grief.

Morning, 1973

My father and his Valiant.

In the driveway, early in the morning, he forces the pedal down.

It coughs, chugs, dies.

And again, until we all hear the car scream and flood, like a horse

crossing a swollen river, but drowning.

My father’s shoes are lost in several inches of snow,

collar is up to the wind,

pale overcoat, just a little too large, hangs past his knees.

He curses at the car. Valiant.

A queer name for this pile of tin, with its weak minded engine, smelly seats and a cracked window.

My father eyes the upstairs window where I wait, still groggy.

He knows he needs to come in and make breakfast for the four children.

That his wife won’t be out of bed this morning – another bad night for her.

Lunches to be made as well.

While he scrambles the eggs he’ll be putting bologna on bread, a streak of mustard across the meat,

a dry slice of aging cheddar.

He’ll place pretzels in small plastic baggies. Grab us each a softening apple.

Yelling periodically for the older ones to get downstairs, to get their boots on, to get me dressed.

The phone rings: the office.

The long kinky green phone cord reaches across the kitchen where he wipes mustard from his tie,

throws a rag for someone to clean up the juice I spilled.

“No problem, chief,” he says to the boss as he kicks the dog out of his way. “I’ll be there.”

Heads back outside to wrestle more with his nemesis.

It reluctantly ignites,

Spews fumes into the frigid Jersey air.

Joe scrapes the ice from the windows and packs us in,

book bags, children, his worn down brief case.

He distributes chap-stick, brown lunch bags, advice.

Drives down the long rocky driveway,

the car sliding in the snow like a drunk.

left, right, then left.

He straightens it out and drives on, turns onto to the snow-quiet road.

He carries all his children, out to the winter day