Q and A with Poet Matthew M Monte

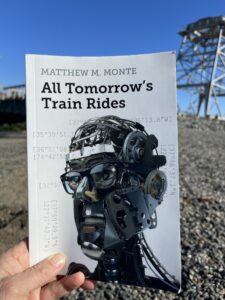

I recently had the pleasure of getting to know a new book of poems by Matthew M Monte, a San Francisco based poet. All Tomorrow’s Train Rides (Sixteen Rivers Press, 2023) employs “poetic cartography,” rich and complex language and images that shimmer in memory long after you have put down the book. I was so struck with the layers that existed within each poem, a combination or geography, history, philosophy and astute observations about the natural and built world. Monte takes the reader on many journeys –sharing his daily train ride south from San Francisco, traveling through parts of Northern Mexico, hanging in his own neighborhood (the Sunset District) and following a trail of bread crumbs through the inner ruminations of the poet.

I met Matthew years ago at a writers conference, (Community of Writers Conference) and recently caught up with him for a Q and A about his fascinating collection. Read our dialogue below, and check out the book itself here.

Joanell: Obviously, this is a stunning collection of poems, that needs to be read and reread in order to understand and absorb the many layers in each poem. It feels like certain poems could have taken years to solidify. There is ample research and this thrilling compilation of science, history, personal history and challenging lexicon. I say challenging because I often reached for my dictionary while reading. Which is perfect. So, as a writer I ask the obvious question—how long were you working on this collection? What was the process like to bring this collection together?

Matthew:

Some of the poems, including the title poem, were started over ten years ago. A few of them have been published in different versions over the years.

The idea for making this collection came to fruition a couple of years ago, just after I published a chapbook called The Case of the Six-Sided Dream. I started seeing how the poem All Tomorrow’s Train Rides could be broken up, like “stops” between other poems.

Those stops are along the MUNI and Cal Train lines I used to take to work. The commute was two hours each way, five days a week. So I got to read 4-5 hours a day. I began to think about the natural and cultural histories the train line passed through, which became new poetic correspondences with some of my older poems.

Joanell: I now live not far from the Caltrain station, which is written about in the poems, and where the trains you write about leave San Francisco and head south. It is a strange place, especially disconcerting and heart breaking at night. You describe the South of Market neighborhood various times:

With the blue glass high rising out of squatter camps

By the Freeway on ramp where 99% shake fist and rattle cups…

….

Graffit glares from all sides, Simple as piss

Marking ones territory

Joanell: Would you say this is the SOMA of pre-pandemic?

Matthew:

The first drafts of the title poem were conceived at the height of the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011. I proceeded to work on that poem (on and off) for nine more years and finished it just before the pandemic. At one point I considered chucking it, but had the good fortune of showing an early version to Jack Hirschman before he passed away. He was very encouraging, so I kept going.

Joanell: Do you think it’s gotten better or worse since the fleeing of much of the tech community to the suburbs and beyond? Were you in a role during the time you were writing these poems that felt connected to the problem in Soma? Or simply an observer?

Matthew:

I think SOMA has declined in the years since I wrote All Tomorrow’s Train Rides. There’s a line, the wrecking ball economy south of Market, which is what it looked like back then. A lot of the old hotels were being leveled. Those were SOMA’s version of low-income housing back then, so scores of people suddenly became homeless. The hotels were replaced with high-rises that in turn housed a lot of tech companies (until the pandemic emptied them out). Now the high-rises sit empty and our most needy citizens are still sleeping in the street.

I was a science writer at a pharmaceutical company back then. I want to believe my work didn’t contribute to the human suffering, but that’s probably naivete on my part. It’s all interconnected. That said, I was not an objective observer. I can’t stand by and witness misery. You could say my poems implore me to get involved. And I don’t mean END HOMELESSNESS or END HUNGER. I don’t pretend to work in any grand manner. For me, it means finding a way to be of service and doing that one thing, even if it’s a small contribution to the amelioration of suffering.

Joanell: Your book was called a poetic cartography in one review I read. There are coordinates throughout the book, relating to the places of which you write, which I found intriguing as someone who is geographically quite challenged. (The REM song, “Stand in the place where you are, think about direction wonder why you haven’t before” always felt like they were speaking directly to me.)

Can you share more about this choice to tie your poems so directly to their geographical coordinates. Is that a window into your own experience in the world?

Matthew:

In addition to maps and map making, I’ve had a lifelong fascination with where people were when they read a particular book. Remembering where and what I read are the twin engines of my autobiography. For example, the first book I ever read in Spanish was a translation of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (El Viejo y El Mar). I read it in when I lived in Chiapas, Mexico. The poet Christian Wiman explores this practice with startling erudition and beauty in his book of essays, Ambition and Survival: Becoming a Poet.

As I explored this idea in poetry, the coordinates of place names in books (such as Castilla-La Mancha, in Don Quixote) became superimposed on the places I was traveling through on the train while I read. This personal cartography of reading then extended into California histories. I read hundreds of books during the years of that commute so I began to create vast memory networks and associations that became poetic correspondences. For me, these place-memories are as atavistic as the original questions mankind’s first maps tried to answer: How did I get here? How will I get there? Can you get there, too, following this path I’ve drawn?

Joanell: You also write of the geography of Mexico, telling stories within the poems, with sprinkles of Spanish. One poem includes the word descanso repeatedly, when writing about a desert area close to the border and in fact write about thinking about this word. “there must be two kinds of decanso”.

You write of the memorial on the side of the road to a girl who was killed by a truck and of the experience of migrants forced to cross the border for work.

An ever-present descanso

pales beside entire families

come to tend trees

In the strange norte

no destiny manifest in the pointing flora

Only dignity and a days work.

Can you share more about your thoughts on this word, Descanso, and/or on your experience traveling in this area?

Matthew:

I start the poem Decanso with a few definitions:

(Noun), (Sp.): 1. Roadside shrine marking a person’s death, where their passing was usually violent, unexpected, or (sometimes) far from home; often decorated with flowers, crosses, candles embossed with images of saints, or other offerings that hint at the manner of one’s death.

2. Stones set at intervals between the church and the cemetery where the pallbearers rest.

3. Relief

Many years ago, my good friend and I drove across Mexico. We started in San Diego and drove all the way to Chiapas, on the Guatemalan border. We saw hundreds of descansos along the way and often stopped to photograph them. Some are quite crude, made of broken car doors and piles of rocks; others are like candle-lit, baroque sculptures. My father is a mortician, so I grew up around people mourning and celebrating the lives of their loved ones. I’ve always been fascinated with these rituals. I think that meditation on death is overlooked or feared in American culture. For me, it’s not grotesque or dark. It’s vital. I believe the many cultures of Mexico have a far more nuanced and rich relationship to death.

Joanell: Write Livelihood hits close to home, as I think it will for any writer:

“Sometimes you tell yourself there is nothing wrong with not writing

People of enviable constitution never give it a second thought…”

Those might be my favorite lines of the poem. All writers struggle with this challenge, when the writing (or life) gets difficult. Why do we do it?

I think it is interesting that the poem is near the end of the collection. I wondered if it signifies the writer is done wrestling and has accepted writing as part of their constitution, as a necessary part of life. Any other insights into this poem or your process?

Matthew:

I’ve kept a journal since I was twelve years old. I’ve always needed to read books and write to expand my consciousness, order my experience, and know what I mean. All the lofty business aside, I read books because they are an inexhaustible source of pleasure. Writing them proves to be more of a rollercoaster, but it seems I couldn’t get off the ride, even if I wanted.

To your question about process, any writing I do is a distant second to my reading. Jorge Borges opens his Biblioteca Personal with this: “Let others boast of the books they have been given to write; I boast of those I have been given to read.”

I spend far more time reading than writing. I can’t write prose for longer than a few hours at a stretch. Conversely, with half a dozen unfinished poems, I could happily work all afternoon. I like the old pen-to-paper for poems, but I also have a hot pink Smith-Corona I’ll bash away on. The computer is my go-to for prose. Once I get a story going, a pen will not keep up with my thoughts.

Joanell: So much of your poetry is intimately connected to San Francisco geography. In Sometimes I Hear Bells, I pictured a world built on sand and assume you are writing an ode of sorts to the Sunset area. It is quickly followed by a poem about 48th avenue, and again I think of the Sunset.

I stare out to the sea

Where the block and land ends

Can you share anything about your experience of writing ‘from” this neighborhood, excavating the history of it, knowing the residents, etc.?

Matthew:

Sometimes I Hear the Bells is about the Sunset District. I have a long history with the neighborhood. I started surfing here in my teens, hitchhiking over from San Rafael (until my friends got cars). I left California in 1988 and told myself that if I ever returned to the U.S. I would live in the Sunset District. I came back in 2006 and have been here ever since.

As you probably know, the Sunset was built on sand dunes. I have yet to track down a primary source, but according to neighborhood lore, Hollywood crews from the 1920’ and 40’s used to shoot desert movie scenes in the Sunset. Either way, I never tire of looking at old photos of this area.

The other poem, 48th Avenue in a Box of Keys, was written in the Sunset at the height of the pandemic. People were leaving the city in droves. U-Haul ran out of trucks. The corner by my house became a spot where people left what they couldn’t fit in their jam-packed moving vans. It was tremendously sad. My old neighbors weren’t dumping garbage. I found beautiful old books, boxes of keys, trophies, framed portraits, antique furniture—objects of clearly sentimental value that people literally could not carry. Some of my neighbors had raised their children in the Sunet and wanted to stay but couldn’t afford to. Some of my neighbors were sick of barely scraping by, living paycheck to paycheck. Some of them thought San Francisco’s best years were long gone. So I poured everything into that poem, that I might preserve their place-memories.

Joanell: Thanks for sharing these insight! I am eager to keep following your writing journeys, wherever they leads.