Holy Tea and Me.

Joanell Serra

Christian Women’s Club meeting, Tuesday 10 AM is written in child-like letters on our family chalkboard. My sister points it out to us at dinner, proud of her efficiency when she took the call earlier, from our neighbor, Mrs. Moore.

My mother slides pork chops onto our plates and rolls her eyes. She drops a dollop of applesauce next to every chop. My father, removing his suit jacket, takes a seat at the table, releasing a sigh. Home.

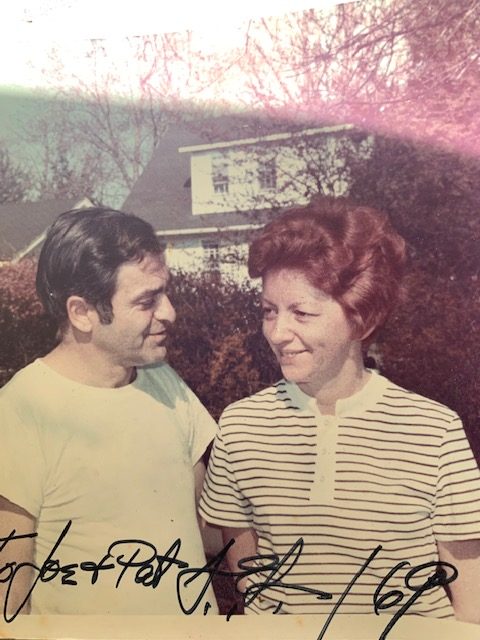

“You’re going to go that, Pat? She’s asked a few times.”

My mother is ambivalent about the Christian Women’s Club. My father is a joiner- from the army to school board to the neighborhood Elks club, he likes to belong. He places his tie over his shoulder so it doesn’t get a spot on it. He will go back out after dinner for a school board meeting.

“I guess,” my mother says. The pork chops are tough. My brother reaches over and helps Mom cut hers up.

The next day I am dragged from my elaborate game of Barbie’s in jail (my own invention) to go to the luncheon with my mother, as we have no babysitter. My siblings watch me in the afternoons and evenings, if my mother is out, but generally she and I are together. I am almost five, and have rejected the concept of pre-school.

My mother had taught me to read by four, and we carry books at all times. At doctor’s appointments, church meetings and PTA gatherings, I read. People say I am an angel. My mother says you should see her at home.

The Christian women have coffee, tea and a blue cookie tin on the table. When they pry the top off of the tin, petite piles of butter cookies are wrapped in crinkling white paper. The scent of vanilla wafts from them.

The women gather in the living room, their stockings swishing as they pass. They hold bibles, reading to one another and talking. A lot of talking. I wait in the dining room, having been situated at one corner of the table with milk, two cookies, and a pile of books.

I shift closer to the door, to make sure I can hear their words. I’m thinking of covens of witches and wondering if spells are a possibility. The women instead speak of sheep, flocks, and the power of prayer. One woman says God has called her. I slip off the chair, moving closer. Does God call people? I picture our wall phone ringing, the long curly cord that can stretch all the way to the stove. I’m not allowed to answer it.

I’ve never heard adults say they talk to God. I talk to God, but that is my secret.

They talk about being saved. From what? I peer through glass panes on the door to see their fluffy hair, wrinkled faces, and the thick bibles resting heavy on their ironed skirts.

“How is your prayer life?” A woman with a mole on her lip asks my mother.

I watch my mother closely. Her brows have been penciled on quickly, one slightly higher than the other. She has smooth skin, unlined. Her eyes are heavily lidded, with small circles under her eyes. Not deep and dark like my grandmother’s, just a mere shadow of her actual weariness. Her red hair, her pride, curls over her collar.

“My prayer life is fine,” she says. I hear something in her voice. She looks out the window, refusing to engage. Are there tears in her eyes? I can’t see well enough. Mrs. Moore’s spotted hand rests lightly on my mother’s shoulder.

Mrs. Moore brings tuna and bean casseroles and lemon cake after each of my mother’s operations. She and her husband have adopted children from all over the world, greatly diversifying the neighborhood. They grow corn in the fields behind their house. Mr. Moore smiles when he sees me hiding in the dry stalks that bend in the wind. They are good neighbors, but seeing her hand resting heavy on my mother’s shoulder makes my jaw set. Mom’s shoulders often radiate pain.

Another woman opens her bible and reads, and the mood shifts. Something makes the room appear lighter. God. Or the sunlight through the far window. I step back.

During lunch, I slip out of my chair and hide under the table. I consider their shoes: black heels, scuffed brown loafers, slip-on sneakers. My mother wears olive green orthopedic shoes, made especially to hold her twisted feet.

I examine the many knees. Small, slim, large, fat, freckled, white, brown. My mother’s knees are scarred, huge train-track stitches mark the sides of each knee. I can’t remember if these knees are new, not really hers. They must be, if they have so many stitches. My finger itch to touch her scars. I know from experience the skin there will be smooth and taught.

Many of my mother’s joints are replacements. Plastic and metal alternatives from a hospital in New York City. I picture the hospital like a shoe store, my mother and her doctor wandering the aisles, looking for a size eight, right knee, with the flexibility required to mother me. To be able to scoop me up and hold me on her hip. To pull me out from under the table, and scold me for looking up the dresses of the Christian women. A joint that would offer the flexibility to get down on the floor and crawl under the table and join me in my den of knees.

But even her replacement knees do not work that well. I see the pain in her face as she bends down to speak to me. Her words are gentle, “Come on out of there now, sweetie.”

Her eyes tell a different story. Are you kidding me? Get out from under the damn table.

Something deep inside me is stuck, angry and stubborn. I shake my head. I won’t come out from under the Christian women’s lunch table. I won’t read quietly. I won’t be good. I will not eat dry tuna sandwiches.

“You can have another cookie,” thee mole mouthed woman bribes me.

I ignore her. Sweets don’t have the needed swaying power.

“Be a good girl,” Mrs. Moore says. Her lipstick cracks in a fake smile. I am upsetting her guests. I hold tight to the center post, the table wide and long. They can’t reach me or get me out without a struggle. I’m small but strong.

My mother’s face comes back, red and flustered. “Joanell, come out now. You can have tea.”

Did she say that? Really?

I’d been asking to try tea for months, begging for it like a New England patriot after the Boston tea debacle. Tea! My resolve slips.

“But only if you come now.”

I scramble out. My mother is always good for her word. My cup is half full with strong, bitter tea. I gulp it, scalding my tongue. My eyes tear up. Mom pours in milk and offers the sugar bowl. I add sugar, stir, add more milk. The women smile.

Praise God, she’s behaving.

Praise God? Praise tea! I slurp it up in minutes. My mother refills, and I drink. Repeat. We stay for another half an hour, leaving when it’s time to collect my siblings.

“Oh I don’t think so,” she declines, when the women ask if she will consider being a regular member.

Maybe she’d like to volunteer with them?

“It’s just too much with this little one.”

They can’t argue with that.

I bounce my caffeine filled body down the long gravel driveway like Tigger on crack. My book bag over my shoulder, I run circles around their front yard. I toss it down and climb one of the trees, howling like a monkey. My mother swoops up my bag and lets me do cartwheels the entire walk home. My hands are sticky with tar and my tights rip.

The next morning, my father crunches on his toast, then rises, grabbing his bulging briefcase. He looks at his wife, remembers something. “The luncheon at the Moore’s! Yesterday? How was it?”

My mother’s eyes slide part way closed when she’s annoyed.

“I think Joanell’s a convert.” Her voice is neutral, even bored. “We’re going to volunteer at the mission next time.”

“That’s great.” My father tousles my hair, proud.

I look at my mother, confused and she winks, pushing a cup of coffee and milk towards me, two sugar cubes on the side. An alliance is formed.

I stir, then take my first drink of sweet, milky coffee.

Halleluiah, praise the Lord. Converted I am.

Love this. Each description is so evocative right down to the dollop of apple sauce. I want to know each of the characters more, especially the little hellion, Joanell!

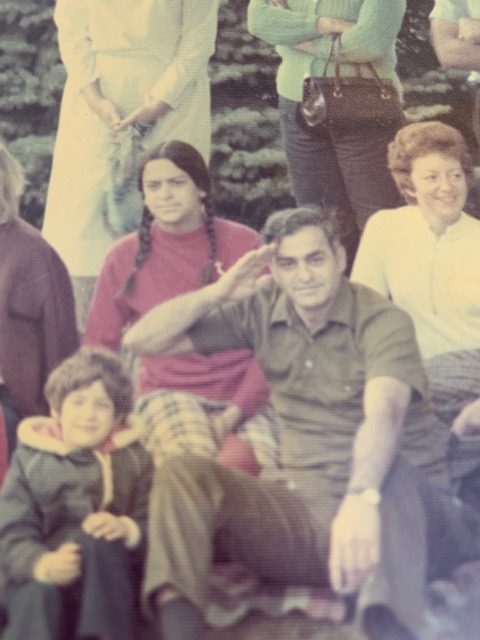

Can’t get over how much Leslie looks like your mom and you look like your dad!!

I enjoyed reading about the inquisitive little five year old.

Tea and milk and sugar (I use honey) heal or help most situations.