I met poet and teacher Robbin Farr several years ago, when I decided to look for an online class break up the pandemic isolation a bit and simultaneously improve my poetry skills (which were sorely lacking. In my mind, the practice of writing poetry was bound to enrich my prose writing. I discovered River Heron’s writing workshops through a poetry contact, and signed up for my first poetry class in many years.

Robbin, the teacher/facilitator, quickly showed herself to be a patient, supportive and inspiring teacher—with a great sense of humor. A few seasons in her class helped my writing immeasurably, although I am still hesitant to call myself a poet.

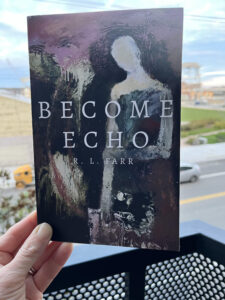

Robbin’s debut collection, Become Echo, came out recently and I have read and re-read it over the last few weeks. What a pleasure to spend time in the hands of a truly gifted poet. Become Echo incorporates themes of love, loss and renewal, frequently weaving in powerful imagery from the natural world. After reading and reflecting on her work she and I had a bit of an email “conversation” about the collection and poetry more generally. See Q and A and helpful links below.

Joanell: Your poems often end with lines that are startlingly good- they really jolt the reader into thinking, reflecting and rereading the poem. I particularly like:

-the last stanza of Cicada …and in sudden and silent retreat/to know how/to leave behind one’s body

-the last 2 lines of Consecrate…fold your life in half now/start from there..

-the last 2 lines of Disproving Physics:Buzzard Bay… Like particles accrete to stars/we bind ourselves to loss…

Can you speak to the decision or inclination to write such powerful endings? Was this something you learned? Mimic from favorite poets? Have you had to go back and rewrite them quite a bit to get such tight lines?

Robbin: How I arrive at the endings of my poems is a bit ironic given how I struggle to put down each line, each word of a poem. Oftentimes the endings seem to appear unexpectedly, and I get a palpable feeling that it is the right ending, the one that must complete and complement the poem. Perhaps the advice of one of my mentors, Dr. Christopher Bursk, remains strongly with me. He said to create an ending that closes with an image or insight, that it must have “payoff” for the reader and must impact the writer in the gut. Or perhaps by the time I am approaching the end of the poem, I have finally entered the flow of creating and by then I am able to tap into that powerful state.

Joanell: This collection feels like a journey, from opening to end. The poems seem to build on one another. Did that happen naturally, written chronologically? Did you use a particular framework in choosing the order? Any advice on this for debut poets?

Robbin: The poems in the collection do indeed follow a journey. That was purposely fostered through numerous trials of rearranging the manuscript over a period of about 5 months. Though the order has an arc, it is subtle. The time period is protracted, but the action is limited. The relationship written about in the book undergoes stagnation and alienation but not in a dramatic series of events. In fact, the poems reflect the speaker’s state of mind as it attempts to understand what had happened rather than telling what is happening. The inclusion of the nature poems does reflect my inclination to refer to natural objects and events, but, in these instances, it is the theme of the nature poem that ties into the themes of the collection. They are purposely chosen to emphasize the universality of the subject of endings. My advice on arranging a collection is to consider many arrangements of the poems rather than grasping onto a preconceived idea. Include thematic poems and seek to have the poems reflect one upon the next. Consider the poems as threads, and it is your task to weave the threads together to make a tapestry.

Joanell: Your titles truly peak the interest of the reader and often introduce the poem. My favorite might be I Ask for Nothing Less than Disaster.

How do you “find” your titles? Do you tend to name your poems last, once they feel complete? Or is it part of the original draft?

Robbin: I am a bit of a stickler about titles! I strongly believe that the title should include some context of the poem. It should be more than a label. It needs to inform and intrigue so the reader wants to read on. If a title falls flat, the reader may not read. My titles sometimes seem to write themselves and other times, struggle for recognition. They, too, go through a series of drafts until I feel a sense of connection.

Joanell: All poets have a landscape they draw upon. I come across he woods of the Northeast in your collection, and spots in Manhattan—Penn Station. Bryant park, Midtown. The natural world is also a major influence in your writing, and we read of cicadas, starlings, constellations, aspens and sweet briar. Can you speak to how place plays a role in the collection and especially the weaving in of the natural world?

We exist within the natural world, and we all have a landscape that speaks to us. To separate oneself from it is impossible. To separate the speaker from the landscape of the events seems likewise as impossible. Perhaps landscape is like another sense. We understand the world through our senses and sensing both the visible and invisible landscape places the events in context. How the location and elements of the landscape augment the event is fascinating to me. They are as integral a part as emotions and actions. In the collection, the events themselves play out against the settings and the settings speak to the events. It’s recollection of the landscape that engenders the wash of emotions and the replaying of events. For me, it’s an unbreakable cycle.

To find out more about Robbin, see her website. And to explore taking classes at River Heron, (which I recommend) check them out here.