Thank you for reading and sharing (Her)oics:Women’s Lived Experiences during the Coronavirus Pandemic. As you will see, various themes emerge in the collection as a whole. Below are examples of each themes from different essays, as well as questions to consider in your discussions.

The Theme of Motherhood

Examples:

Maria Ostrowski shares a sweet moment with her son in her otherwise anxiety ridden day in her essay Play with Me, “Make funny faces in the mirror!” Every time Julian and I walk up the stairs, he gives my hand a little tug and we stop to stick out our tongues or scrunch our noses at ourselves in the wall mirror. He laughs every time. Whatever else is happening, we have his moment. A pause in the climb.”

In Azalea Victoria Livingstone writes about the baby she has had, who had been in the Newborn ICU at birth. “She is thriving now, but everything else feels uncertain…I worry about the stability of my job in the wake of severe budget cuts. We can’t visit friends or family, can’t take Azalea to the playground to try the swings for the first time, and certainly can’t travel. I miss the in-person communion I might have had with other new parents and wish my daughter could see her cousins and surviving grandparents—the kind of contact I never had growing up in an immigrant family. I worry that this period of isolation will affect her development, though she won’t remember the pandemic and may never know that she was the force that sustained me.”

In Phone Calls from My Son, Janet Johnsons’s essay, readers get to know her son TJ, who she cannot visit in his group home due to the pandemic. She describes heart break of being the mother separated from her child, even an adult child. “Every night, TJ calls me from his group home on the cordless phone.As he tells me about his day, I imagine the striped bedspread I bought him and the Special Olympic medals hanging on his wall. “I miss my day program,” TJ says, then adds, “I miss you.”

E.K. Bayer writes about her experience jumping in as a home school teacher of twin boys in Relativity. “Who am I, if I can’t get my kids to do their schoolwork? A new, inner voice answered. I am my kids’ support, their shelter, the one interested in what inspires them, not in forcing them to suffer through work too disconnected from its source to carry meaning. I am Mama.”

Alicia Mosley shares insight into the experience of Mothering while Black in Covid 19. “The bodies on the screen were my children’s bodies, my father’s, mine. I was confronting the fear that as my children went out as young adults into the world, racism would take them from me.”

- Did you relate to these experiences?

- Do you think the pandemic stressed mothers, particularly?

- Do you imagine parenting being shifted permanently by the pandemic?

The theme of Mental Illness, and Recovery

Examples:

In “Breathe Through the Pain”: Pregnancy Amid a Pandemic, Kit Rosewater experiences the crippling anxiety of being pregnant during the pandemic, “I send my mind back to January, a world now far away and dreamlike. I twist the waves back into waves of labor. I push away the staggering riptides of panic attacks and grief. I peer into the distance. I try to see you on the horizon.”

Syd Shaw writes about recovery after leaving an abusive relationship in A Shelter of One’s Own, “I didn’t expect anything to come easily after my escape, but the second the veil lifted the pain in my shoulders went away and I started listening to my own music again. . . It was a recovery, a bringing back of limbs long atrophied, a renewal of confidence, friendship, and connection.”

Camille Beredjick writes in ED-10, “Before the pandemic I was in year five of recovering from an eating disorder. I thought constantly about what my body looked like and what others thought of it, but I could quiet the critical voices in my head enough to eat, move, and live how I wanted. In the midst of the pandemic, I’m not sure what recovery means anymore.”

And Alison Hart throws some humor at the situation in her Pandemic Quiz.

“Question 2: Anxiety often keeps you awake, so you refill your old Xanax prescription; everyone else is feeling anxious, too.

You: a) Encourage everyone to brainstorm creative ways to manage anxiety, including yoga, meditation, long walks, painting, baking, and warm baths. b) Stockpile mood-altering substances: dark chocolate, Sumatran coffee, your current house red, and cheap vodka. c) Hide the Xanax in your wardrobe because you don’t want your children to think you use drugs and you absolutely don’t want them to use drugs. Especially not your Xanax; you have a limited supply. d) When your children are chatting about how weed really takes the edge off, admit to having Xanax but tell everyone you hardly ever use it.”

- Did you find these explorations reassuring?

- Did you find compassion for the writers?

- Were you curious about their choices? Worried or relieved?

The Theme of Family History

Examples:

In Reflections on my Grandmother’s Costume Shop while Anxiously Making Masks, Melissa Hart writes:

“I inherited my grandmother’s iron, as well, broken on one side and revealing the inner workings of the machine. When I was thirty, a stage four cancer diagnosis elicited my grandmother’s bemused groan from her hospital bed. With our family around her and no costumes in sight, she performed an E.T. puppet show with the red-lit pulse monitor on her index finger.”

Mary Powelson’s essay A.I.R. shares her mother’s experience during another national health crisis:

“In 1943, the landlord subdivided the family flat on Henry Street, a shaded lane between Noe and Sanchez. A man moved into what was once their living room. He had a bad cough. (Stop thinking about coughs.) In January 1944, in the middle of her fifth-grade year, my mother got tuberculosis. My mom was hospitalized, isolated with strangers, in the TB ward of San Francisco General Hospital until 1949. (A little girl. Five years in lockdown. Think on that.)”

Karen Rollins writes about deriving courage from her family in A No Stay-at-Home Order State: Living with Underlying Conditions during COVID-19. “These battles freshen the memories of my grandmother and aunt’s health struggles. A doctor’s poor care resulted in my grandmother’s losing her eyesight to glaucoma when she was in her early sixties. …My aunt came into contact with acid as a toddler and as a result her mouth and jaw were left twisted and scarred… Both have been guiding lights as I’ve faced my own health challenges. And even though I feel scared, challenged, and powerless during this COVID-19 crisis, I’m inspired by their courageousness.”

- How did you see family history demonstrated in the essays?

- Did you connect with one of the stories that talked about grandmother’s, ancestors and family culture?

- Do you have relatives that lived through similar hard times, and have you thought of them during this time?

The Theme of Facing Racism and Xenophobia

Examples:

In Melba Nicholson Sullivan’s essay Birthright to Breathe, the writer considers lack of adequate care she and her community faced during the pandemic.

“Friday, April 17, 2020 When he struggled to breathe, three NYC hospitals turned away our friend, Jonathan Ademola Adewumi. The fourth admitted him and put him on a respirator. Today he died.”

Ella De Castro Baron writes in her essay Bahala Na, “Instead of recognizing our willing and dedicated labor, those of Filipinx descent are coughed on, yelled at, spat on, forbidden service, even stabbed, because we—the monolithic Asian—“brought the Chinese virus” to the United States. Over 1,700 incidents of anti-Asian 191 discrimination have been reported across forty-five states within the first two months of the shelter in place.”

Tia Oros Peters, in her essay The Ancestors Already Know: Prophecy and Regeneration in a time of Pandemic, writes “Indigenous Peoples all over the world are suffering during this pandemic. Our villages and communities are hot spots. Not because we represent a population “at-risk and vulnerable,” but because for centuries—and, indeed, still—our Peoples have been forcibly put in high-risk and oppressive conditions.”

- Did any of these resonate?

- Did you learn anything new about the experiences of others who do not share your race or culture?

- Did you notice a rise of xenophobia during this time?

- Did any of these essays motivate you to make a change?

The Theme of Loss

Examples:

In Jo Varnish’s The Avocado Plant, she writes about her children’s father, recently passed. “I am back in our Manhattan apartment, those early nights when jet lag and adventure woke us both in the small hours. We’d lie in the darkness, whispering as we listened to the Goo Goo Dolls album he’d bought me for the song “Broadway.” Giddy independence coursed through us. I need to talk to him about that time. I have lost my co-rememberer.”

In On Isolation, Hannah Keziah Agustin writes of the loss of a close friend by suicide, “She chose, in her anguish, to say, “It is finished.” We didn’t check up on her. We will carry this for the rest of our lives. If only humans had the capacity to show love in tangible and straightforward ways, maybe we could’ve kept her here a bit longer; but love is messy and chaotic, hidden, difficult, and selfish.”

Alissa Hirshfeld writes about grieving her prior life, being “newly single” in the pandemic, in her essay, Learning to be Alone in Social Isolation. “Among all the images and stories of death that surround me, I am slowly grieving my old life. As society enters a new COVID-19 reality, negotiating what life will look like in this new terrain, I am figuring out what my new single, soon-to-be empty-nest life will look like. And I am reminded that grief is simply love with nowhere to land.”

- Which stories stood out to you?

- Were you surprised by the way some of the writers dealt with the issue?

- Did you connect with their pain, or enjoy the sweetness of their celebration of the loved one’s life?

The Theme of Resilience

Scrappy, by Joyce R Lombardi, shares the story of a group of women in Baltimore who organized an army of “sewistas” who created hundreds of masks. “Sometimes it felt like we were winning. Like when hospital workers started posting pictures of themselves, thumbs up, wearing our masks. Or when one of Lisa’s contacts, a developer-turned-savior with connections to China, donated 10,000 disposable masks. Within twenty-four hours Lisa and Kim dispatched a tiny fleet to deliver boxes of these imported gems around the city. In your face, supply chain.”

Raluca Loanid writes about her work as a nurse in North Carolina in What is Enough?. In this excerpt, she is testing workers at a tomato canning factory. “The workers I examined looked at me with fear and pleading in their eyes. They asked questions I could not answer like, “Do you think I have the virus?” “How will I support my family if I am off work?” “What will happen to me if I get sick?” “How can I protect my babies?” The vulnerability behind their questions, and my inability to protect them from COVID-19 or bring fair wages and working conditions to the tomato plant, underscores that I am definitely not a hero.”

Kristin Marinovitch writes about her experience as a nurse in a hospital in The One that Hurts Less. “It was astonishing how hard we had to fight to get appropriate protection for ourselves and our families. It felt as if we were soldiers being sent to a war without guns, or firefighters being sent into burning buildings without a breathing apparatus. My husband pleaded with me to resign. But I didn’t want to leave, I wanted protective equipment.”

In Prayers for a New Reality, Shizue Seigel uses her tools as a writing teacher to push back on the loneliness of artists of color. “It’s been a month and a day since the shutdown. With no money and no staff, I’ve served 130 writers through four events. Several pieces that began in our round-robins have been published or performed. The San Francisco poet laureate’s pick for the library’s COVID Poem of the Day on May 14 comes from our group. Two pieces are accepted into this anthology.”

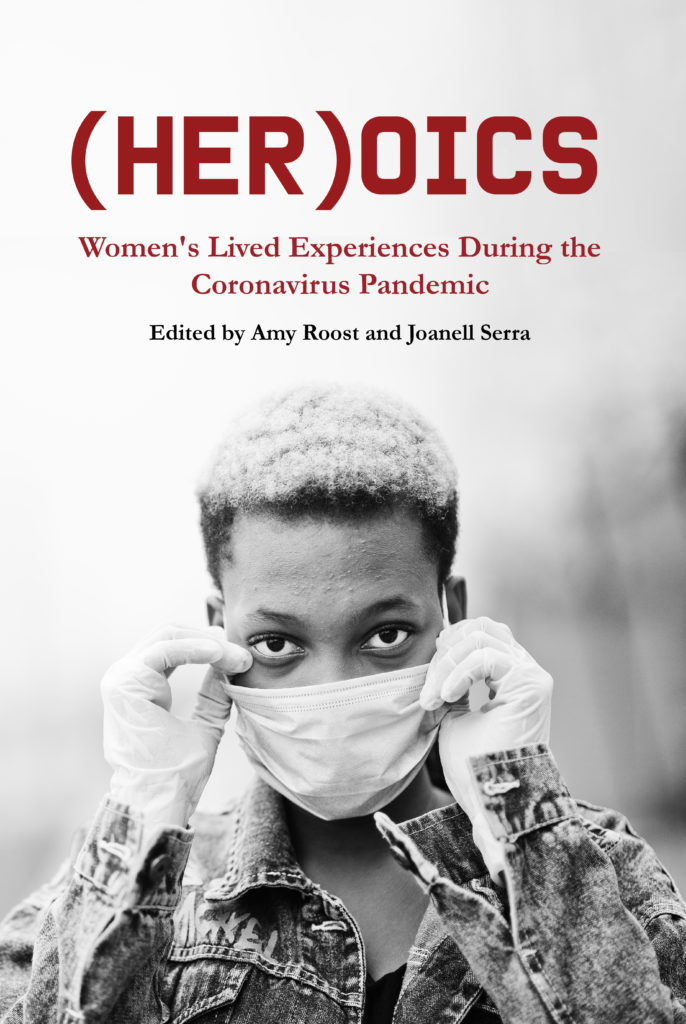

- The title of the book is (Her)oics.

- Did you feel these writers were Heroic? Brave? Resourceful?

- Which story resonated and inspired you?

- Did you find the pandemic motivated you to help others in some new way?